Leninopad

Statues can die, too. Or, as Anna Jermolaewa shows in her film Leninopad, they can be cleared away from their public sites in an alleged act of liberation. This frequently creates a gap that can be occupied by various diffuse, often no less awkward ideological motifs.

Jermolaewa embarked on a journey through the Ukraine, traveling to extremely diverse settings to document the (always already completed) fall of now incriminated Lenin statues. Following the political upheaval in 2013, the statues were stormed, even before the so-called de-communization law officially sanctioned this type of symbolic murdering of the past in 2015. Throughout the entire country, statues were knocked off their plinths, their torsos were cut in half, they were decapitated, and the attempt made to bury or otherwise hide the fragments.

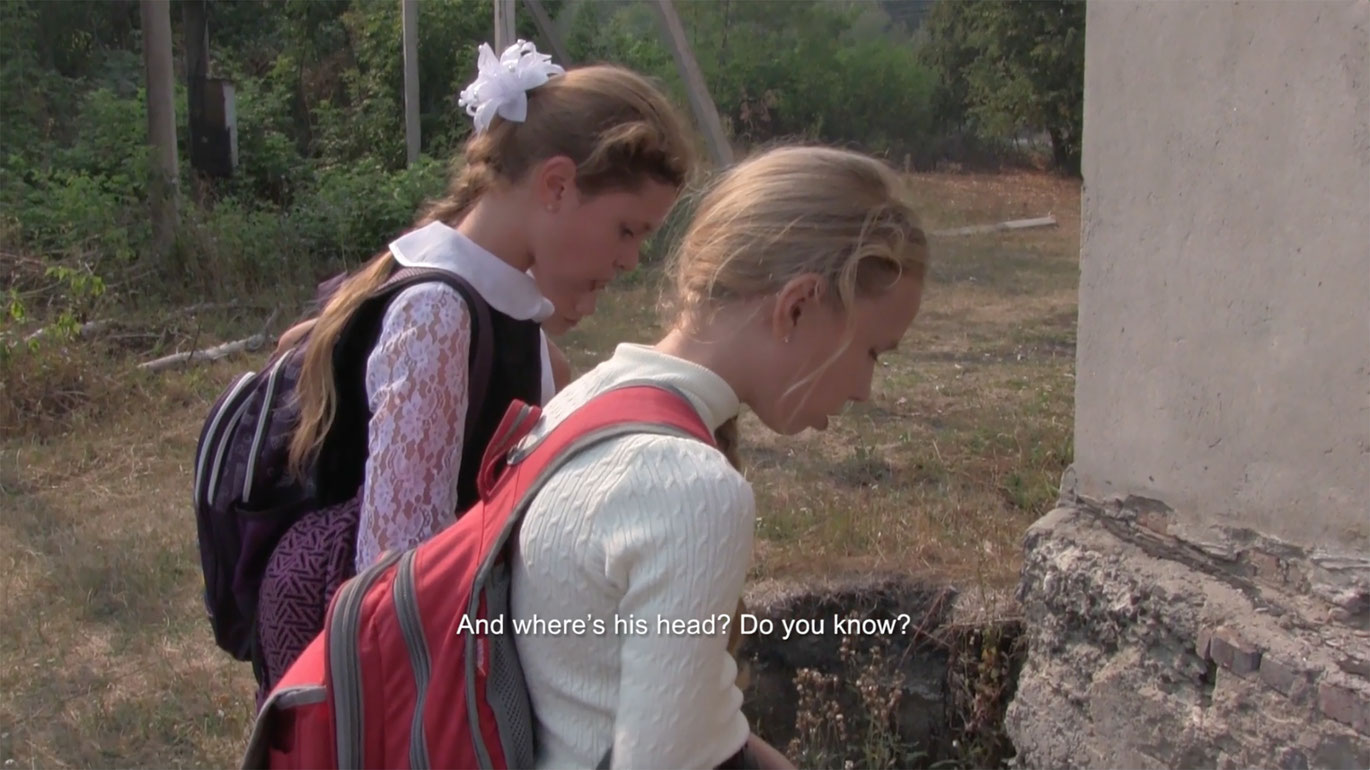

In her coverage of the phenomenon, Jermolaewa seeks contact with locals and inquires into the course of events of the demolition. The pattern that thereby comes to light is usually the same: none of the interviewed women, peasants, or children claim to have seen much, in most cases those doing the demolishing ("foreigners," from "somewhere else") carried out their work speedily at the crack of dawn; in most cases, the people seem somehow in agreement with what happened; after all, old Lenin (and with him, Stalin) has half the country on his conscience.

Following the conversations, what the film shows in static, thoroughly admonishing photos is just as expressive: empty plinths, which are mostly covered with neo-nationalistic, folkloristic, or church décor. Yet often only a roughly hewn base remains, a type of ideological emptiness that bears witness to the still raging trench warfare.

The statues in which people see the ghost of the past might have been eliminated. But that does not at all mean that enough space has now been created for freedom and democracy. (Christian Höller)

Translation: Lisa Rosenblatt

Leninopad

2017

Austria

22 min